|

|

|

- Hisaya Morishige, the Great Hiratsuka Air Raid and Houzenin -

Ryuko Matsushita, Chief Priest of Houzenin

March 10, 2010 |

[Japanese Page]

|

|

Last November, Hisaya Morishige, known as the doyen of the Japanese entertainment

world, passed away at the age of 99. Many paid tribute to the memory of

the great actor. One of them was Mikio Haruna, a journalist and professor

at the Graduate School of Languages and Cultures, Nagoya University. His

article, published in the November 20, 2009, issue of the Nikkan Gendai

tabloid, was very unusual.

"Morishige participated in Covert Operations at the U.S. Embassy"

was the title of Haruna's article. He wrote: "For a certain period

during the postwar years, Morishige was engaged in a secret task assigned

to him by the radio department of the U.S. Embassy in Tokyo." According

to the professor, the task was part of psychological operations conducted

by the National Security Council (NSC) to "make Japanese people like

the U.S." Haruna also argued that the secret operations proved very

successful and continued until 1971, with the participation of Morishige

and other prominent actors and actresses of the time, including Ayuro Miki,

Mariko Miyagi, Michiyo Yokoyama and Meiko Nakamura. In fact, a hidden purpose

of the post-war operations was deeply linked to the large-scale air raid

on Hiratsuka City in 1945.

The Great Hiratsuka Air Raid occurred less than a month before the end

of the war. From midnight of July 16, 1945 to the following day, Hiratsuka

was attacked by 138 B-29 bombers of the U.S. Air Force flying in formation.

The city was bombed so heavily that a resident of a neighboring town, who

lived in a house with a good view of the destroyed city, said later, "The

city was burning like anything. It was so bright outside that I could read

a newspaper late into the night." That night, 8,000 of the city's

10,419 houses were burned down and 343 people died. Houzenin, our temple,

also went up in flames and was completely destroyed.

|

| B-29 Superfortress bombers dropping incendiary bombs. |

|

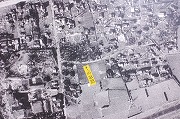

| Photo of Houzenin's neighborhood taken just after the air raid (by the

U.S. Air Force) |

| At that time, I was only one-and-a-half-years old. With me on her back,

my mother ran with my grandmother through furious fire for Oiso, a neighboring

town where our relatives lived. As my mother told me when I grew up, all

we could do that night was reach the bridge to Oiso, 700 meters away from

our temple. We spent a sleepless night under the bridge over the Hanamizu

River. Though it must have been an important target, the bridge just managed

to avoid being hit by a bomb and we survived; or the U.S. Air Force may

have left it as it was on purpose, in order to use it for their subsequent

landing operations. In those days, when going to sleep at night, my mother

used to place our temple's Kakocho (Buddhist death registers) wrapped in

a cloth at the head of her bed, so that she could carry it with her in

an emergency. She ascribes our survival in the rain of bombs to the Honzon-sama

(main deity) of Houzenin, the Kakocho and our ancestors. The devastation

caused by the air raid was so complete that it was only natural for her

to think this way. I have no idea what was registered in my memory, but

for some reason, I still do not like the United States. Perhaps etched

deep in my memory is the sight of my mother with a baby on her back running

frantically for a way out of the red tongues of flame. |

|

| Hiratsuka city war dead memorial |

|

| Peace memorial inscription |

The U.S. Air Force had two bombing strategies: carpet and screw attacks.

In the case of Hiratsuka, the latter was used. This is how a screw attack

is made. First, a bomb is dropped in the center of the target area. Then,

bombs are dropped one after another in a clockwise spiral. Curtains of

fire are created and the people surrounded are likely to die from lack

of oxygen and intense heat. Such indiscriminate killing of civilians apparently

violates the Geneva Convention. The bombardment Hiratsuka suffered is called

the "Great Air Raid" because more bombs were dropped (447,716

incendiaries, 1,173 tons in total) than in the Tokyo Air Raid of March

10, 1945 (380,000 incendiaries). According to the Japanese Edition of Wikipedia,

the air raid on Hiratsuka is second only to that on Hachioji (a city in

southwestern Tokyo) in terms of the amount of bombs dropped per unit area.

Considering the fact that 8.2 incendiaries were dropped per resident, the

death toll was notably low. For one thing, there were quite a few evacuees

from Tokyo, who had experienced air raids in the capital and passed on

their "survival know-how" to Hiratsuka residents. In addition,

Hiratsuka was then a farming area and many fields separated the houses.

For these reasons, not as many people died in the fire as in Tokyo, where

some 100,000 people died on March 10 alone.

On the morning after the horrible bombing, so worried about us, our relatives

in Oiso came to our temple to find that it had been completely burned down.

They cried out my mother's name at the top of their voices, but in vain.

Thinking that we were all burned to death, they returned home with their

hearts in their boots. They told me the story when I was old enough to

understand things.

Years later, I entered nearby Fujimi Elementary School. Yokohama Rubber,

Nissan Shatai, Sankyo and other companies built their factories on the

burned flat land and many workers moved in with their families from around

the country. When I was a fifth or sixth grader, our elementary school

was so crowded that some pupils (including me) transferred to a branch

school. The makeshift school was in a building that was once a boarding

house for workers of the Hiratsuka Naval Ammunitions Arsenal. (During the

postwar years of recovery, there were no other buildings available in the

city.) On the wall of our classroom, there was a message in black ink:

"Meet me at Yasukuni Shrine (as the war dead)," perhaps written

by a young soldier who was going to war. During recess, we often picked

up bullets. Come to think of it, we shanty dwellers in the burned ruins

lived just the way war orphans in Baghdad do now.

From back then, there was a deeply held belief among Hiratsuka residents,

which still remains. It claims that U.S. forces bombed Hiratsuka in order

to destroy the Hiratsuka Naval Ammunitions Arsenal. People born in my generation

have been told about the story ever since we were young children, and I

think most of the residents still accept it. My friends and I believed

it all the more because we went to the arsenal-turned school every day.

|

| Officers' Lounge, Hiratsuka Naval Ammunitions Arsenal memorial structure |

The Hiratsuka Naval Ammunitions Arsenal occupies an important place in

Japanese military history. As the nation's first gunpowder plant, it was

jointly built in 1905 by three British companies: Armstrong Whitworth,

Novel and Chilworth. The explosives produced here were used in the Russo-Japanese

War (1904-1905). Ironically enough, only a few decades after its inauguration

through the efforts of British architects and supervisors hired for the

project, the arsenal was bombed and destroyed by the Allies, including

the United States and Britain. And the bombing thrust the citizens into

the deadly throes. Now there is a factory on the site.

The U.S. freedom of information act is said to be a recent big headache

for the Japanese Foreign Ministry. Based on the act, U.S. diplomatic documents

are disclosed after a certain period of time, regardless of the contents.

They may reveal secret agreements with the United States and behind-the-scenes

maneuvers of the Japanese Foreign Ministry playing dumb with the public,

including deals regarding the transport of nuclear weapons into Japan and

the reversion of Okinawa to Japan. This reminds me of the well-known joke

of a popular manzai stand-up comedian couple: "If it cannot be found,

let's keep it a secret." Despite the ministry's doga-chaka attempts

to keep the maneuvers secret from the public, the U.S. disclosure act gave

the whole show away. (Doga-chaka is a cliche used in a famous rakugo comic

story to explain the way the general manager of a store doctors the accounts

so that he can keep his fingers in the till.)

Materials covering the Great Hiratsuka Air Raid, were also disclosed

by the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) 50 years after

the tragedy. An acquaintance of mine visited NARA to browse the materials

and returned with some surprising news. Despite a widely accepted belief,

the U.S. Air Force didn't care at all if the ammunitions arsenal was destroyed!

Near the end of the war, the crew of a Grumman spy plane reported that,

for lack of materials, plant workers did not manufacture explosives but

grew potatoes to survive. An arsenal that produces potatoes-what a joke!

For young readers' information, Grumman Aircraft Engineering's fighter

aircraft were American counterparts of the "Zero" fighter. In

Japan, U.S. fighters were collectively called "Grumman".

Harking back to his childhood, a man about ten years older than me often

said proudly that he had been pursued and shot at by a Grumman fighter

while at the beach and in the schoolyard. He said, "The guy at the

controls of the Grumman flew out of sight, sneering at me." (Many

children were killed miserably in such a manner.) In other words, Grumman

aircraft flew to Japan very often for aerial surveillance. They had already

known that the arsenal was producing potatoes instead of explosives.

Now I remember that some elderly people said that on the morning of the

day the war ended, August 15, 1945, there were countless U.S. warships

off the coast of Hiratsuka. How do the facts relate to each other? The

disclosed U.S. documents answer the question.

|

| US Marine warships in Shonan. |

According to the documents disclosed by NARA, there were four reasons

behind the Hiratsuka air raid:

| - |

Hiratsuka was intended as the beachhead for the landing operations. |

| - |

Learning the bitter lesson of the ground battle of Okinawa that killed

many U.S. soldiers, the U.S. forces planned to clear all the buildings

from the beachhead so as not to provide enemy snipers with a place to hide. |

| - |

Any Japanese survivors were to be killed with sarin nerve gas. |

| - |

After landing on Hiratsuka, soldiers were to make a beeline to the north

as far as Hachioji, before turning right and reaching central Tokyo along

the Chuo Line railway. (The plan explains the connection between air raids

on Hiratsuka and Hachioji. In the early hours of August 2, 1945, Hachioji

was attacked by 170 B-29 bombers that dropped 670,000 incendiaries, which

burned 80% of the urban area and killed 450 residents.) |

|

| Naval Ammunitions Arsenal memorial tablet |

Now we know that Hiratsuka was bombed to establish a beachhead, not to

destroy the ammunitions arsenal. So why did Hiratsuka citizens believe,

for decades, that their city was attacked because of the potato-producing

plant?

Among the General Headquarters' occupation policies was the War Guilt

Information Program (WGIP), developed to convince the Japanese people that

the responsibility for the war lay with them. The program was led by Earnest

Hilgard (1904 - 2001), a professor of Stanford University, and Milton Erickson

(1901 - ). I am not sure if you know that, but the two are the 20th century's

leading experts in the field of hypnosis and brainwashing. These experts

delivered a grand educational program to brainwash the people of Japan

into believing that they themselves are responsible for and guilty of the

whole tragedy of the war (including the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and

Nagasaki). Jun Eto (1932 - 1999), a critic and professor of Keio University,

compiled his research reports into a book after a lifetime of work. The

cover of the book "Closed Language Space: Censorship by Occupation

Forces and Postwar Japan" (Bunshun Bunko paperback published by Bungeishunju

Ltd.) says:

"Japan lost World War II and was occupied by the U.S. forces. The

victor carefully prepared for and enforced censorship in the defeated nation,

in order to destroy Japanese ideology and culture completely. As a result

of the censorship program, 'a loss of self' among the Japanese public led

to self-propagation of a new taboo."

As far as the Great Hiratsuka Air Raid is concerned, WGIP was intended

to convince the citizens that they were responsible for the bombing of

their city because it would not have been destroyed if they had not built

the gunpowder plant there. In this way, the United States made an attempt

to draw the citizens' attention away from the canceled invasion operations

including the sarin attack plan. I think the trick turned out to be a great

success, for most of them have believed for 60 years that the city was

attacked because of the plant. The secret operations by the U.S. Embassy

with the help of Hisaya Morishige, which I mentioned at the beginning of

this report, were part of the grand project of Japanese occupation related

to WGIP. Now most Japanese people seem to like the former foe very much,

and I must say that WGIP was a huge success.

References

1. Aerial photo of Houzenin's neighborhood taken just after the Great Hiratsuka

Air Raid (original stored at the National Archives and Records Administration)

2. Officers' Lounge, Hiratsuka Naval Ammunitions Arsenal memorial structure

3. Hiratsuka city peace memorial dedicated to those who died in the war

including air raid victims

4. US Marine warships in Shonan (original stored at the National Archives and Records Administration)

5. Hiratsuka Naval Ammunitions Arsenal memorial inscription

6. Mainland invasion campaign and sarin gas attack plan

In April 1945, Franklin Roosevelt died of a stroke and Harry Truman took

office. The 33rd U.S. President gave approval to "Operation Downfall",

the Japanese mainland invasion campaign, which was canceled because of

Japan's surrender earlier than expected. Hideji Okina, a freelance writer,

writes about their extraordinary plan in his article "U.S. Air Forces

Planned to Use Sarin Gas in Invasion of Japan", published in the August

17 and 24, 2006 combined issue of the Shukan Shincho weekly magazine. The

campaign consisted of two stages to secure Japan's unconditional surrender:

Operation Olympic, the invasion of southern Kyushu (Japan's third largest

island) with 820,000 soldiers, and Operation Coronet, the invasion of the

Kanto Plain containing the capital, with a million soldiers. The writer

argues that the U.S. forces, intimidated by Japan's desperate resistance

during the ground battle in Okinawa, decided to make elaborate preparations

for landing: saturation air raids, intensive naval bombardment and extermination

with sarin gas. The U.S. Navy shipped almost 60,000 poison gas bombs to

the front-poison gas bombs were supposed to account for 20% of all the

bombs for the campaign. The estimated death toll from Operation Olympic

was one million and that from Operation Coronet was several million. The

Great Hiratsuka Air Raid was nothing but a sign of the beginning of Operation

Coronet for the invasion of the Kanto area.

The local residents' story about an enormous number of U.S. warships

seen on the morning of August 15, 1945 fits the explanation of Operation

Coronet. Is it a miracle or a prank that I, born in Hiratsuka in 1944,

survived the deadly air raid, escaped the poisonous attack and write this

report now?

- Afterword -

During the war, many Houzenin officials were killed and in the end, the

entire premises were burned to ashes just before the war ended. The previous

chief priest suffered great hardships to reconstruct the temple. I think

these are honest questions Japanese people have in their minds: Why did

they have to face such reckless deeds? Why did many lives have to be lost

so miserably? And I also wonder why all the halls and pagodas of Houzenin,

including valuable cultural treasures, had to be destroyed. As one of the

survivors of the horrible air raid, I put together my long pondered questions

into this report.

As far as I feel at this time, a remote cause of this tragedy seems to

lie in the way political power was shifted during the Meiji Restoration

(in the late 19th century) as well as the character of those who grabbed

power.

|

|

|

|

|